• Lola Solís • IDRA Newsletter • September 2021 •

This article describes IDRA’s examination of the relationship between out-of-school suspensions, specifically, and high school non-completion rates in Texas public school districts. Using Texas Education Agency (TEA) and U.S. Department of Education Civil Rights Data Collection (CRDC) data, we fit a regression model to examine one key question: Do higher out-of-school suspension rates lead to higher rates of high school non-completion?

According to TEA, in the 2017-18 school year, over 1 million students faced exclusionary disciplinary practices. There were 5,073 expulsion actions in Texas, 437,518 out-of-school suspensions, and 1,128,906 in-school suspensions in 2018-19.

Student groups do not face exclusionary practices equally. According to the U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights, Black students are three times more likely to be suspended or expelled than White students. And 16% of Black students experience suspensions compared to only 5% of White students. Though they represent less than 1% of the student population, American Indian and Native Alaskan students also are disproportionately suspended and expelled, making up about 2% of out-of-school suspensions and 3% of expulsions. (OCR, 2021)

Data and Analysis

We combined aggregate district-level data from TEA and CDRC for 2017-18. The combined dataset includes data on district enrollment, out-of-school suspensions and dropout rates. The combined file contained 1,204 observations, including both public school districts and public charter schools. We limited the analysis to public school districts only and kept only the cases with complete data. Our final analytical sample was 342 Texas traditional public school districts.

To examine the relationship between out-of-school suspension on high school non-completion rates, we fit a multivariate, ordinary least squares regression model predicting school districts’ high-school non-completion rates. The key independent variable was districts’ out-of-school suspension rates with control variables for percent Hispanic, Black, White, Other, and economically disadvantaged student enrollments.

Exclusionary discipline in schools has adverse effects on students’ attrition, graduation, state assessment test performance and dropout rates.

Key Study Findings

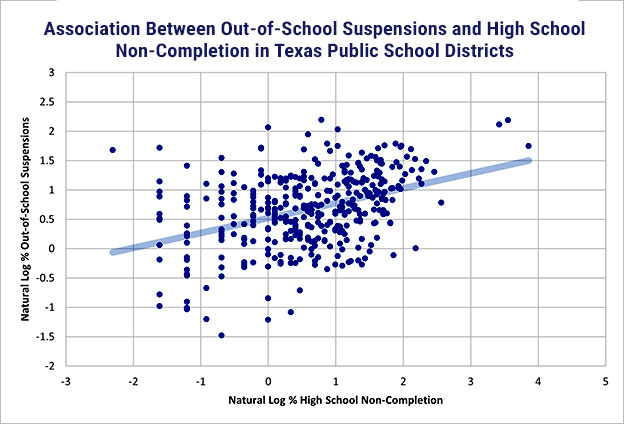

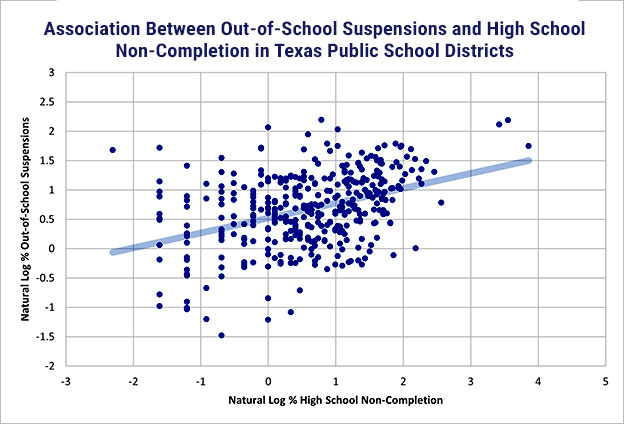

In the sample, the median school district percentage of out-of-school suspensions was 2.1%, and the median school district percentage of high school non-completion was 1.7%. The graph below shows a positive, linear association between the two key variables in the data. As the rates of out-of-school suspensions increase, the rates of high school non-completions also increase.

Put differently, among Texas school districts in the sample, higher rates of out-of-school suspensions are associated with higher rates of high school non-completion. Among Texas school districts in the study, a 1% increase in out-of-school suspension was associated with a 1.4% increase in high school non-completion, with all else held equal. Additionally, a 1% increase in the Latino and Other enrollments were associated with 1.4% and 1.1% increases in high school non-completion, respectively.

Policy Recommendations

Exclusionary discipline practices negatively impact students’ dropout rates across districts in Texas. Additionally, exclusionary practices result in racial disparities, with Black students and Latino students experiencing suspension at higher rates than their white counterparts.

Schools should implement more impactful alternatives to exclusionary practices that will not result in increased dropout rates.

Following are three suggestions for educators (Ramón, 2020).

- End policies and school practices that create hostile school environments for students. Schools should work to keep students in class every day and should never send students to disciplinary alternative education programs for minor violations of student codes of conduct.

- Increase the presence of counselors, social workers and nurses. The average academic counselor had 424 students under his or her watch, according to the American School Counselor Association (2021), which recommends a 250:1 ratio.

- Direct funds for teachers and administrators at home campuses to support students. The legislature should increase funding for research-based supports and programs in schools to help keep students in class.

School leaders should focus on addressing root causes of discipline issues and incorporate restorative approaches to maintain school health and successful students in public school districts.

Resources

American School Counselor Association. (2021). Student-to-School-Counselor Ratio 2019-2020. Factsheet. Alexandria, Va.: ASCA.

Balfanz, R., Byrnes, V., & Fox, J. (2012). Sent Home and Put Off-Track: The Antecedents, Disproportionalities, and Consequences of Being Suspended in the Ninth Grade. Journal of Applied Research on Children: Informing Policy for Children at Risk: Vol. 5 : Iss. 2 , Article 13.

Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law. (2017). Fact Sheet: Positive Behavior Supports (PBS) and School Achievement.

Centre for Justice & Reconciliation. (2019). Tutorial: Intro to Restorative Justice. Washington, D.C.: Centre for Justice & Reconciliation.

Center on PBIS (2021). Positive Behavioral Interventions & Supports, website. www.pbis.org.

NEA. (2021). Policy Statement on Discipline and the School-To-Prison Pipeline, 2021 NEA Annual Meeting. National Education Association.

Teicher Khadaroo, S. (March 31, 2013). Restorative justice: One high school’s path to reducing suspensions by half. Christian Science Monitor.

Office for Civil Rights. (2021). 2017-18 Civil Rights Data Collection. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Education.

Lola Solís served as a summer intern with the IDRA research and evaluation team in 2021. She is earning her master’s with a focus on public policy at University of California, Berkeley.

[©2021, IDRA. This article originally appeared in the September 2021 IDRA Newsletter by the Intercultural Development Research Association. Permission to reproduce this article is granted provided the article is reprinted in its entirety and proper credit is given to IDRA and the author.]