By Makiah Lyons • Knowledge is Power • February 7, 2023 •

Since 2021, several states have enacted curriculum censorship laws, limiting how teachers can teach issues of race, racism and other ideas deemed divisive or uncomfortable. Growing campaigns to ban books from public schools and libraries have also targeted books with themes of race or racism.

Last month, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis’s administration sent a letter to College Board rejecting its new African American history course, calling into question its legality and – perhaps even more troubling – its educational value. The College Board released the official curriculum framework on February 1 and, while much of the original content remains, many contemporary topics have been removed.

Black History Month was created not only as a celebration of Black History but to encourage truth-telling and the development of culturally sustaining school curriculum so that Black children may understand themselves and their past and be prepared for their future.

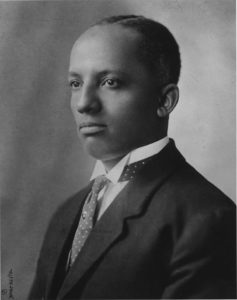

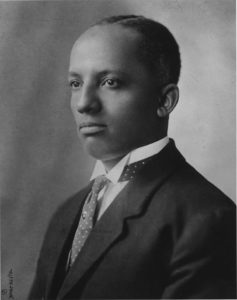

Black History Month would not have been possible if not for the work and legacy of Carter G. Woodson, a man often called the “Father of Black History.” Woodson was a teacher and scholar. Born in Virginia in 1875 to parents who were formerly enslaved, Woodson had little access to education and helped his family by working on their farm and in coal mines as a teenager. Woodson taught himself several school subjects and saved money to attend high school at the age of 20, graduating only two years later. He would go on to become a teacher and a school principal before earning a Ph.D. from Harvard in 1912. Woodson was the second Black American to earn a doctoral degree, after W.E.B. DuBois.

Woodson advocated for African American History as a serious scholarly discipline to be taught as a part of school curriculum, finding that the historical contributions of African Americans were “overlooked, ignored and even suppressed.” Though Woodson was a member of the American Historical Association, he was barred from participation in their conferences. Woodson knew that more historical research centering the lives of African Americans was necessary but found difficulty in having his own research and writings published by predominately white scholarly journals and publishers.

Because major publishing companies were disinterested in publishing works of African American history, Woodson founded a publishing company in 1920. The company published articles, collections of short stories for youth, and books including Woodson’s most famous work, 1933’s

In 1926, Woodson and his organization created Negro History Week, a celebration to honor the contributions of Black Americans and encourage the teaching of Black history in public schools. Fifty years later in 1976, Negro History Week would be expanded to the entire month of February.

Woodson also wrote and published African American history textbooks used in classrooms across the country. In 1928, Woodson adapted an advanced textbook into simple language to meet the needs of younger students. The book entitled Negro Makers of History was advertised as the first African American history textbook for elementary-level students.

In 1937, Woodson created the Negro History Bulletin, a monthly newsletter published in plain language for teachers, students, families and the public. The Bulletin allowed educators to share their classroom stories, included articles about notable Black figures in history, provided book recommendations for children, and had dedicated pages for children’s content.

Woodson continued producing textbooks and educational materials for educators and students of all ages until his death in 1950, providing rich and diverse perspectives that challenged the negative narratives and stereotypes about Black people dominating popular history books.

As we consider how best to celebrate Black History Month this year, may we all be encouraged and inspired to pursue truth. May we tell Black stories of both triumph and tragedy, as complex or uncomfortable as they may be, with courage and conviction. May we seek out the stories we have not yet discovered and uncover the stories not yet told. We will all be better for it.

“Real education means to inspire people to live more abundantly, to learn to begin with life as they find it and make it better” – Carter G. Woodson