• Aurelio M. Montemayor, M.Ed. • IDRA Newsletter • February 2021 •

Who better can attest to their ingenuity than students themselves? I asked some students for recommendations and interviewed four remarkable teachers. I spoke with them to see how they combine instruction of challenging content with creative use of applications to engage the students.

Annabel Saenz Cruz, La Joya ISD

Annabel Saenz Cruz teaches freshman biology at Palm View High School in La Joya ISD in South Texas.

She said: “It is a huge struggle for the student to sit in front of the computer for an extended period of time for all subjects. We have to be very precise in the delivery of the material.”

In speaking about science specifically, Ms. Cruz said: “Biology has challenges with vocabulary and concepts.” She supplements the textbook because the vocabulary is difficult for English learners.

“When I combine the textbook with Amoeba Sisters and then add slides or an interactive journal, the kids are able to see it in different ways,” she described. “Giving it to them in a way where they are able to be visual and grasp the concept is crucial.”

In speaking with students, Ms. Cruz said: “I remind students about the perks and benefits of the technology they have grown up with. In college and in life, technology is everywhere. Before, we didn’t have much technology in our schools. Now it’s: ‘Here’s your own Chromebook. Let’s type out the report. Let’s go ahead and share the document. You’re going to be working on it with so-and-so on the project together.’ I’ve always wanted to use technology in the classroom.”

She said: “I plan to integrate some of these apps in face-to-face teaching. We can communicate even after school when some students miss. They can you log in later on get the lesson.”

Jennifer Schulze-Aguirre, Northside ISD

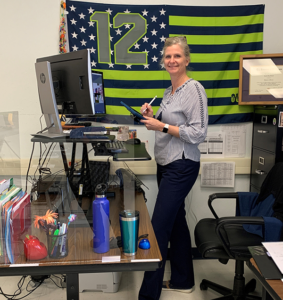

Jennifer Schulze-Aguirre prefers to teach standing up. Teaching students online did not change that. She uses an extendable desk and a second monitor to be able to see her students while teaching. She also uses a tablet so that students can see her walk through calculus demonstrations. She said, “I have more energy and that gets translated to my students!”

When schools first closed last March, teachers had no time to prepare for the shift to distance learning. During the summer, as they got ready for the new school year, they applied what they learned during the previous spring.

Jennifer Schulze-Aguirre, who teaches Algebra 1 through AP Calculus BC at Brandeis High School in San Antonio, described: “First, I took multiple deep breaths myself because so much a part of who I am is interacting in person with my students. I had to figure out a way to make it still happen. How am I going to make them feel comfortable taking calculus, especially in a virtual environment? What kinds of things can I bring across in a Zoom meeting that would be somewhat the same as what I would do in person? I wanted to make sure I knew everything to make it more efficient for the students and make sure that it is easier for them to do the work.”

Math is the subject that is proving to be most difficult for students to progress through distance learning. Ms. Schulze-Aguirre described how she adapted to support students who are online: “I normally do a lot of matching activities in calculus and had to figure out how to do that virtually; I learned how to do Google drawing very well. “In my in-person classroom, I could walk around, hear students talking in their groups and fix misconceptions on the spot. But now I don’t have that ability. I have them do daily practices, and I spot check them. And I do individual tutoring appointments for students who need it.”

“When someone contributes, she acknowledges us and praises us by name, even if our camera is off.”

– Leslie, student

Ms. Schultz-Aguirre encourages parents: “Ask questions about how to help your son or daughter engage in learning. Have patience with their teachers, because just like the students, they are having a hard time struggling with what is happening.”

And for her teacher peers, she encourages: “Remember the impact that you have. It doesn’t matter if you’re virtual or you’re in person. What you say, how you act, how you interact with your kids, it says something to them. And you may not know the impact you have on them for a couple of years. That impact is probably even more important now that kids are isolated socially. Just remember, your words and actions mean so much to your kids.”

Bertha Amaro, La Joya ISD

Bertha Amaro is a precalculus and precalculus pre-AP teacher and math department chair at Palm View High School in La Joya ISD in South Texas.

“A big challenge is having everything hands on,” she said. “In the regular classroom, everyone had their calculators out. I could see what they were doing in person. With online calculators, it is difficult to see what they are doing.” Constant feedback is crucial to learn if your student is better at visual or audio learning or another type of learning and to adapt your style.

She advises other teachers: “Don’t try to do everything you learned over the summer or in a couple of trainings, to do everything at the same time. Take your time. Do one application. Learn it well and keep going. Have patience because some of the students are not logging in. And it is not because they don’t like the teacher. It often is because maybe their situation at home doesn’t allow it.”

“I always try to tie the lesson to what’s going on in our lives so they can fully understand.”

– Annabel Saenz Cruz, biology teacher

As Ms. Cruz mentioned, distance learning is particularly challenging for emergent bilingual students. High school teachers must create ways to support students in learning new complicated academic vocabulary.

Ms. Amara said: “I have to do my lesson in English, of course. But during the one-on-one 20-minute period, I work with my students who are English learners. Precalculus is a totally different language, because you use such big and high words.” Her students ask for the technical terms in Spanish. “The calculus terms go beyond even the algebra vocabulary they already know in Spanish.”

Thomas Ray García, South Texas Lower Rio Grande Valley

Thomas Ray Garcia discusses college preparation with high school students.

Thomas Ray García supports students in several high schools in the South Texas Lower Rio Grande Valley with steps to prepare for college and the application process.

He described the various ways he connects with students online: “I am currently jumping into Google Meets classrooms and Google Classroom. I invite students to share each other’s screen, review essays and apply to colleges. The fact that we are both staring at a screen and looking at the same tab actually helps.”

“You can cut down on direct instruction using a hybrid of maybe 15 to 20 minutes of synchronous activity and then an asynchronous activity,” Mr. García advises. “The student works in the Google Classroom conducting a poll or doing a piece of writing for 10 to 15 minutes and then jumps back into the Google Classroom to continue talking about it. It breaks the rhythm.”

High school juniors and seniors do not have time to miss content or to catch up later. “It’s hard keeping students on track with deadlines that are outside of our control,” Mr. García said. “College applications are pretty on the nose. One of the challenges is making sure all the work we assign students is scaffolded where one task completed leads to another.”

Technology will be a good partner for teachers’ personal connections with students. Mr. García said: “I love working with the students one-on-one over Zoom. I get to see their screen in real time, and we talk about specific sentences word by word. The students light up when they discover something and write a sentence that they’re truly proud of.”

Mr. García advises parents, “Keep in contact with the teacher once or twice a month at least. I hope that continues after the pandemic when students literally do go away from home, back to school and the parents cannot see the lesson going on anymore.”

One common thread among the four teachers was the use of two-way communication with students. They listened to each student and modified their teaching to reach each one. Without simplifying the subject, they adapted the content so that it would be understood in the new learning environment. All were supportive of direct, personal contact with the students and their families and were available for help, consultation and conversation. The students valued teachers’ encouragement the most.

Students: Jaasai and Leslie

Jaasai said of Ms. Amaro: “In this overwhelming time period, my teacher has been very patient and understanding with my classmates and me. She makes sure everyone is understanding and answers all of our questions the best she can.”

Leslie said of Ms. Schulze-Aguirre: “When someone answers a question wrong, she explains why it’s wrong. And once a week, she posts a “check of understanding” worksheet so we can see for ourselves how we’re doing before a test.”

Both, Jaasai and Leslie said their teachers post their slides and instruction videos online for students to review later. “And she really, really wants us to do one-on-one tutoring with her when we need it, Leslie added. “She keeps telling us she wants her timeslots to be full.”

Jaasai said: “She leaves a private chat open 24/7. She is always double checking if we need any help or have any questions even after we have said no. But some students are shy about asking a question, so she stays after class for students who are having trouble with the lesson that day.”

Similarly, Leslie said: “She stays on Zoom the whole class period to be available for questions. During class, she is very engaging. She asks questions, and we have to respond. She checks to make sure we’re understanding something and watches her screen to make sure everyone nods or something. Students who don’t have their cameras on have to do the thumbs up emoji. She asks for feedback, and if we don’t understand, she’ll explain it differently until we do. And she covers every step.”

When Lourdes Flores asked her teens about their teacher, they described her constant encouragement, including encouragement to keep their cameras on. From her own vantage point, Ms. Flores appreciates their teachers reaching out to parents seeking their support from home. And she is grateful for the patience of the teachers to attend to all the difficulties of technology and connection issues.

Some of the students’ feedback sounds simple at first, like teachers answering student emails quickly. Leslie added, “When someone contributes, she acknowledges us and praises us by name, even if our camera is off.”

Teaching via distance learning has been a challenge and an opportunity. Effective teachers have new ways of teaching and explore the benefits of digital access to enhance one-on-one communication. They connect student interests and experiences with learning of concepts. In the virtual classrooms of these four teachers, students are engaged and learning high-level math and science during the pandemic.

Aurelio M. Montemayor, M.Ed., is IDRA’s family engagement coordinator and directs IDRA Education CAFE work. Comments and questions may be directed to him via email at aurelio.montemayor@idra.org.

[©2021, IDRA. This article originally appeared in the February 2021 IDRA Newsletter by the Intercultural Development Research Association. Permission to reproduce this article is granted provided the article is reprinted in its entirety and proper credit is given to IDRA and the author.]